In my last post, I talked about the challenges associated with keeping my rainforest mind sufficiently busy as a child. I shared that one thing I would do if I didn’t have a book or other form of writing around me to read was to hum a tune in solfege – defined by MusicTheoryTutor.org as:

… a system where every note of a scale is given its own unique syllable, which is used to sing that note every time it appears. A major or a minor scale (the most common scales in Western classical music) has seven notes, and so the solfege system has seven basic syllables: do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, and ti.

Americans will probably be most familiar with solfege from Maria von Trapp (a.k.a. Julie Andrews) singing “Do-Re-Mi” around the streets of Salzburg with her wards in The Sound of Music (1965) (one of my all-time favorite movies). The song teaches solfege through the following homophones:

Doe, a deer, a female deer

Ray, a drop of golden sun

Me, a name I call myself

Fa, a long long way to go

Sew, a needle pulling thread

La, a note that follows Sol

Tea, a drink with jam and bread

That will bring us back to Doe

Once the solfege “alphabet” is acquired and rehearsed, it serves as a magical key to the musical universe. Every single melody (at least in Western music – other scales and systems have their own unique entryways) can be “solfeged” – and since I was also studying piano as a child (my choice – I insisted on lessons), I would often combine solfege with moving my fingers in the air or on my legs as though playing over a keyboard.

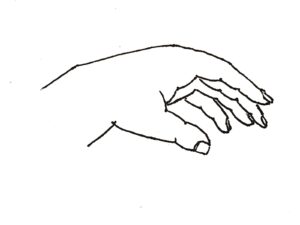

In addition to solfege, I engaged my fingers and mind with chisanbop, a Korean-developed method of counting to one hundred on one’s two hands (right hand = ones, left hand = tens). Chisanbop came to America at just the right time for me to learn it as a first grader, at which point I very quickly become ultra-proficient, spending my recess time experimenting with ways to multiply by various numbers. (Sadly, none of my friends seemed particularly interested in watching or participating, so I recall simply doing this on my own.)

Chisanbop went out of style in schools shortly after this, for reasons I’ve never understood – but I never lost it, and have continued to use my hands to count (and subtract, multiply, and divide) to this day.

As a fun side-story, I ended up being given the nickname “Chisanbop” during a volunteer teaching gig a couple of years ago at a minimum security men’s prison. My co-instructor and I were offering a series of modules on learning and leadership, and I used chisanbop as a literally hands-on example of how one might learn and teach something new. The guys were super-intrigued, and many took to it quickly – though one in particular, D., struggled quite a bit. Each time D. came to follow-up classes, he greeted me with a smile, said, “Hey, Chisanbop”, and gave me an update on how he was proceeding with his practice – which included trying to teach it to other men in the prison to get better at it himself.

I mention both solfege and chisanbop together in this post to highlight just two of the ways I kept my brain creatively engaged as a sensory-minded, twice-exceptional kiddo – without realizing at the time that this was what I was doing (or why). In hindsight, I can see how integrally connected these both were with embodied cognition: that is, I was desperate to make a connection between what my brain was cycling through (knowing/learning math and music), and how this might manifest bodily in the world (through my fingers).

I use the term “desperate” because as fun as these activities were, they sometimes felt almost like addictive and/or compulsive tendencies. I consider them a form of “coping OCD” that eventually went away. (I’ll write more about this in another post, since there’s a lot more to say about OCD and gifted kids.)

But most of the time, solfege and chisanbop served me well. Chisanbop gave me an always-available way to quickly count points during games, for instance, while solfege became the foundation for a much more extensive understanding of musical theory – which proved surprisingly useful in college.

As I wrote about in a previous post, I went to college because I knew I needed a bachelor’s degree of some kind to go on and get a teaching credential – but I wasn’t clear on what to study, or why. I ended up majoring in literature and minoring in music simply because I liked them both, despite not really understanding (at first) what either of these specializations entailed.

It turns out that studying music at the college level meant not just performing but really getting into the weeds of how music is constructed – i.e., the nuts and bolts of its existence, which includes taking solfege to a whole other level. In one of my beginning music theory classes, we had an infamous “64 Intervals Test” that was conducted orally in front of everybody. One at a time, we were given 64 different intervals, both ascending and descending, and asked to name each one. I completed my test perfectly on the first try – probably in no small part because I’d spent my childhood solfegging non-stop inside my brain. In future quarters of more advanced music theory, we were given portions of simple Bach chorales and asked to dictate the chords we heard; this was harder, but I still did well.

Since I was minoring rather than majoring in music, I wasn’t required to give a performance in the “big concert hall” – a good thing, since I was just barely getting myself up to performance-speed and didn’t feel nearly confident enough to pull something like this off. While I’d spent years loving music in the abstract, I knew I wasn’t cut out for a career in performance.

With that said, my interest in unusual music intrigued my piano instructor, who had never before worked with someone fascinated by early twentieth century American composers like Samuel Barber and George Antheil. My instructor encouraged me to put on a “Fridays at Four” concert in the music building, which was much lower-stakes, and allowed me to share the stage with a fellow student.

I performed part of Antheil’s “Airplane Sonata” and several of Barber’s “Excursions”, practicing just enough to prove I could put on a reasonable show, but knowing this would be my “last hurrah” with both piano concerts and getting anywhere close to “perfection” – which it was. A handful of my good friends came to watch me and took me out to lunch afterwards. I still remember this fondly, and regret not having a recording of it to watch. (This was a different era in technology.)

I spent a good many years after this wondering why, exactly, I’d chosen to study music, since I never planned on making a career of it. Many moons later – after lengthy deliberation and reading about the value of liberal arts degrees more broadly – I’ve come to realize that there was nothing at all “wrong” about choosing to study music for awhile, as opposed to anything else. Something about its innate structure and beauty struck me as worthwhile – and that hasn’t gone away. Music continues to be almost like magic to me: it’s so powerful I almost can’t bear it at times. I actually have to stay away unless or until I’m ready to engage and get lost in it. (I need to write another post about music, since there’s so clearly so much more here to process and explore.)

As for chisanbop – while I love having 100 digits available to manipulate on just two hands, I didn’t end up pursing mathematics beyond Pre-Calculus. I spent one hour in a college-level calculus class, found it less intuitive than I wanted, and gave up, never to return. I went in a liberal arts direction instead, and figured if I ever needed or wanted calculus in my life for some reason, I could come back to it.

As a parent now, I watch my three kids with deep curiosity, checking to see how math and music are playing out in their lives. They all take lessons on various instruments, but I don’t push anything too far, and they don’t seem driven. Meanwhile, none have taken up chisanbop, either, so I guess that really does remain my own unique bailiwick.

Obsessions take on different forms, and my kids’ interests are so clearly different from my own. They code and world-create like nobody’s business, making my mind spin with the quickness and intensity of it all – and so it goes with generational evolution; life (and parenting) are never not fascinating and ever-shifting.

Copyright © 2020 by HalfoftheTruth.org. Please feel free to share with attribution.