As I’ve noted previously, the body of literature about adult giftedness is fairly small, presumably because of (at least) the following two assumptions:

1) We have a legal and moral responsibility to support and nurture gifted children and teens (who are minors under our care), but there is no such formal mandate to continue this support through adulthood.

2) If giftedness is defined as asynchrony between intellectual capacity and other developmental milestones, this developmental asynchrony must presumably come to an end and converge at some point – in other words, a grown person ultimately “catches up” to their intellect and can simply proceed from there – right?

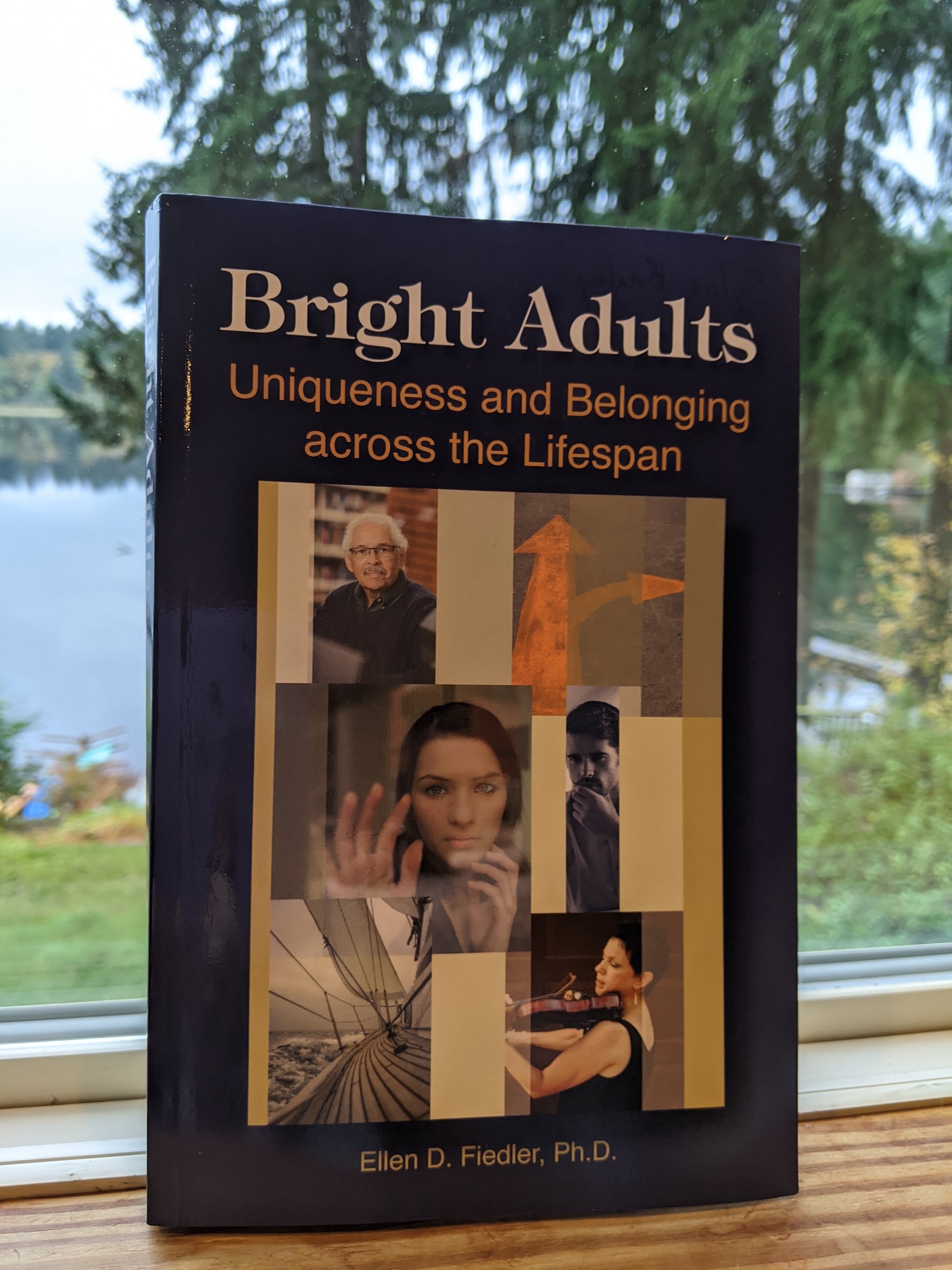

Of course, it’s not that simple – and in Bright Adults: Uniqueness and Belonging Across the Lifespan (2015), Ellen Fiedler directly addresses this through her emphasis on developmental stages for gifted adults throughout their lifetimes.

Fiedler highlights and defines the following six distinct phases of gifted adulthood:

- Seekers: Usually 18-25, on a quest to find their place in the world

- Voyagers: Usually ages 25-35, purposely journeying through life to establish themselves

- Explorers: Usually ages 35-50, matching their lives to their identity and priorities

- Navigators: Usually ages 50-65, using prior knowledge, including self-knowledge, to fulfill their goals

- Actualizers: Usually ages 65-80, on a path of self-actualization as well as helping others actualize their goals and dreams

- Cruisers: Usually age 80 and beyond, using minds that remain intensely active regardless of physical changes

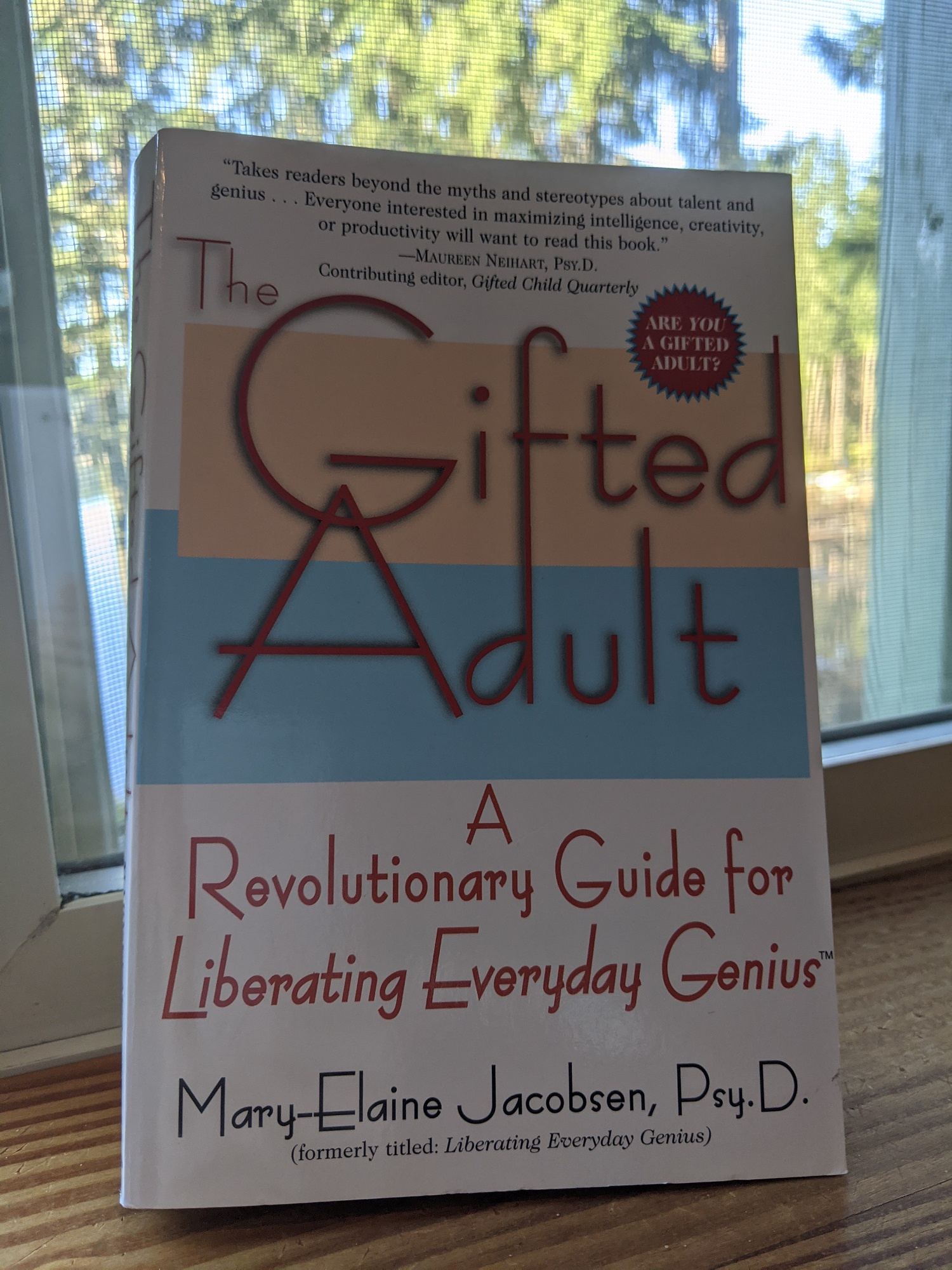

Before proceeding, I’ll briefly share some of Fiedler’s own discussion of how she developed this model. In Appendix 1 (pp. 217-219), she notes that she was inspired by Erik Erikson’s work on adult development; David Shaffer and Daniel Levinson’s publications on “seasons” of an adult’s life (early, middle, and late); Mary-Elaine Jacobsen’s The Gifted Adult (1999); Marlou Streznewski’s Gifted Grownups (1999); Willem Kuipers’ work on XIP (Extra Intelligent People); and Gail Sheehy’s classic book Passages: Predictable Crises of Adult Life (1974, and updated).

Back to Fiedler’s model: she writes that what bright or gifted adults at all these six stages have in common is a tendency to “search for answers about how to live their lives and directions they should go” (p. 2). She notes that such individuals “are usually intense, idealistic, complex, multifaceted, strong-willed, and impatient”, and points out that they “seek to discover if they are ‘there’ yet – that indefinable place where they can find meaning in their lives.” She posits that “in the same way that gifted children often hit their life stages earlier and more intensely than other children, so do gifted adults” (p. 3)

(A ha! Asynchrony again.)

As someone who is constantly questioning my own life and decisions, Fiedler’s acknowledgement of how tumultuous this journey can be is a welcome balm. It’s difficult to explain exactly how painful it is to live with a relentless sense of existential angst and wondering. While of course it can be a beautiful and wondrous thing to question the complexity and mysteries of existence (this is what I hope to see in my own kids!), it can also lead to paralysis, depression, and deep fatigue.

Fiedler takes time early in her book to clarify how common it is for gifted individuals to question their own traits, and to resist a designation of giftedness due to either “fear of failure to live up to the label” (p. 10), fear of being seen as arrogant, heightened sensitivity to perceived disapproval, and/or continuous comparison of one’s own talents or gifts to those in other (distinctive) fields.

(Gifted adults tend to focus on what they haven’t done, rather than what they have done.)

Fiedler provides a useful overview of “significant needs and issues throughout the lifespan”, which include:

- Acceptance

- Meaningful connections

- Living with intensity (either intellectual, sensory, imaginational, and/or emotional)

- Access to resources

- Relevant challenges

- Finding meaning

Next, in Chapters 4-9, Fiedler covers each of the gifted adult developmental stages, including “waypoints and strategies” to help gifted adults navigating through typical challenges and needs. Here are the stages:

Ages 18-24: Seekers (Heading Out): Seekers are on a quest to “find somewhere in the world where life is the way they think it really should be” (p. 43). They are typically “dealing with gaining greater clarity about their identity, overcoming isolation, finding relevant things to do and think about, making college and career choices, coping with entry-level courses and jobs, finding like-minded mentors and colleagues, [and] dealing with newfound freedom” (p. 55).

Ages 25-35: Voyagers (On With the Journey): Voyagers are journeying through life to establish themselves, often “with more purpose than they had as Seekers, even though they are not necessarily tied to specific destinations” (p. 68). They may experience “bore-out” (the self-explanatory flip side of “burn-out”), and are often dealing with or seeking out “the complexity of identity, career decisions and career moves, advanced training, mentors, relationships, [and] parenting” (p. 82).

Ages 35-50: Explorers (Setting a Course): Explorers are matching their lives to their identity and priorities, and often “barely have time for snatching a bit of conversation in the midst of busy, busy lives” (p. 97). Fiedler points out that life for gifted adults “at this stage may look quite different… than for others in the general population because of the characteristic intensity of these bright adults” (p. 98). For instance, while “most people between the ages of 35 and 50 simply want to settle into a comfortable life with a good, solid job and enough money to pay bills each month”, “explorers want more”. Issues faced by Explorers during this stage include: “coping with hectic lives; dealing with higher standards than others; questioning everything about their lives; reevaluating patterns of thinking, behaving, and responding to others; developing lives that fit with their emerging worldviews; [and] dealing with major life events” (p. 108). [As someone who’s been in this stage for awhile, I can attest to all of this as being super-accurate!]

Ages 50-65: Navigators (Smooth Sailing or Stormy Seas): Navigators use their prior knowledge, including self-knowledge, to fulfill their goals and “typically” (though not always, of course) “have increased clarity about their personal goals and values” (p. 117). Waypoints and strategies named by Fiedler at this stage include “coping with conflicting feelings and asynchronous development; using prior knowledge, including self-knowledge; responding to an urgency to accomplish something worthwhile; dealing with dissatisfaction; balancing everything in their lives; [and] setting a new course in life” (p. 124).

Ages 68-80: Actualizers (Making a Difference): Actualizers are on a path of self-actualization in addition to helping others actualize their goals and dreams. This is a time “for bright adults to determine what activities they really want to be involved in so that they can spend their time on their deepest interests and passions”. Hallmarks of this stage – all positive, by the way! – include “reflection, enjoying deeper clarity about their identity, seeking ongoing opportunities to expand their knowledge, connecting with others, [and] generativity” (p. 144).

Ages 80+: Cruisers (Sailing On): Finally, Cruisers have minds that remain intensely active regardless of physical changes, and know who they are and what they want in their remaining years. They move along at a speed that works for them, take care of what’s most important, and may have to respond to ageism. Typical issues dealt with at this stage include “being selective about how to spend their time and energy; continuing to have vibrant, interesting lives; dealing with physical changes; intense drive to exercise their minds; having meaningful relationships with others; remaining independent as much as possible; generativity; [and] being ‘ageless'” – that is, tuning out people who expect you to “act your age” (p. 167-168).

In Chapter 10, Fiedler addresses the issue of “the invisible ones” – i.e., gifted adults who fly “under the radar” – from a variety of perspectives. First she discusses the issue of “stealth giftedness” – that is, those whose giftedness “was never recognized, encouraged, or nurtured”, or those whose “abilities somehow disappeared from sight”, either temporarily or permanently (pp. 183-184). In a section entitled “Rough Going”, she outlines three ways gifted adults may “avoid confronting existential issues”:

- “Moving away from” – i.e., “avoiding and rejecting traditional society by withdrawing”;

- “Moving toward” – i.e., accepting society’s traditions by conforming but remaining “prone to feeling as if they are imposters and, later in life, to feeling that their efforts have been shallow and without meaning”;

- “Moving against” – i.e., “rebelliously rejecting society” (p. 186).

Fiedler acknowledges that the invisibility of some bright adults is due to “complex causes”, including:

- “difficult experiences in childhood or adolescence” (p. 187);

- gender-conformity struggles (pp. 189-193);

- “differing abilities and disabilities” (pp. 193-194);

- mental illness (pp. 194-195);

- personal choice.

Fiedler talks readers through a list of (mostly healthy!) strategies that can be used by “the invisible ones” to cope with their challenges. These include:

- Accepting giftedness;

- Dealing with overwhelming options;

- Numbing themselves to pain (not healthy!);

- Dealing with gender-prescribed roles;

- Coping with how they learn and process information;

- Finding a satisfying, meaningful life.

This is all much easier said than done, of course, but Fiedler’s final chapter at least offers an acknowledgement of the many entry-points invisible gifted adults might take “in order to have satisfying and meaningful lives”, – and, critically, she reminds us it’s “not necessary… to achieve lofty levels of fame and fortune” (p. 208).

What remains under-discussed in Fiedler’s book (and Jacobsen’s) is the issue of “invisible” gifted adults whose lives go so far afield they end up in prison. Streznewski does acknowledge this possibility in her book, so I’ll return to her work as a starting point for a later blog post on that topic.

For now, I’ll close by saying that it was refreshing to see myself reflected in the earlier stages of Fiedler’s model; reassuring to know that my hectic life right now is on par with other Explorers; and eerie (but comforting) to know that older age will bring its own unique opportunities for happiness and satisfaction.

Reference:

- Fiedler, E. (2015). Bright adults: Uniqueness and belonging across the lifespan. Gifted Unlimited, LLC.

Copyright © 2020 by HalfoftheTruth.org. Please feel free to share with attribution.