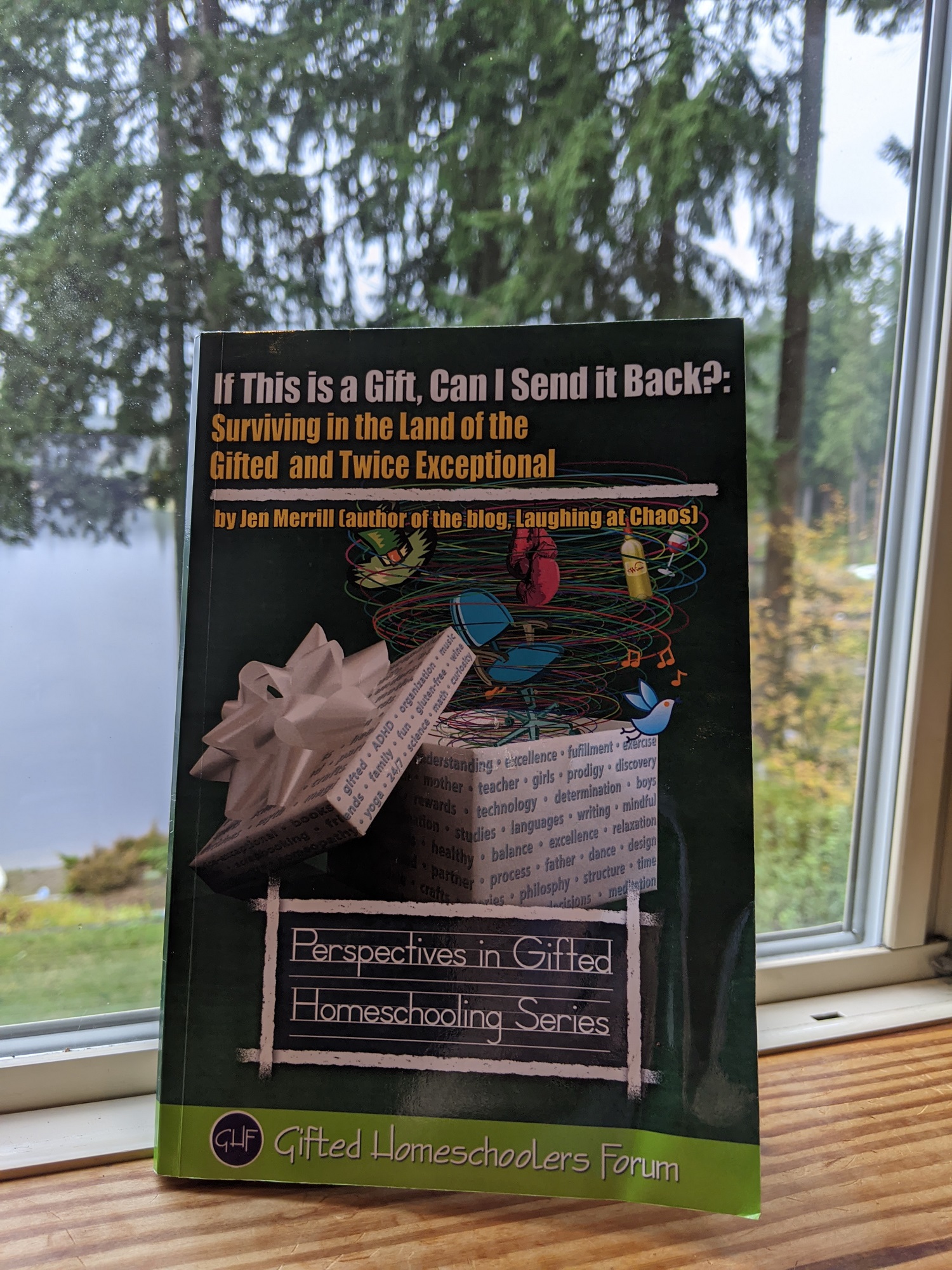

As my second Book Reflection blog post, I thought I would comment on If This is a Gift, Can I Send it Back? Surviving in the Land of the Gifted and Twice Exceptional (2012) – a delightfully humorous and insightful book by Jen Merrill, author of the Laughing at Chaos blog and interviewee about parenting self-care on the Mind Matters Podcast.

On the back of her book, Merrill asks us:

When is life like a prize fight, a garden, and a quiz show, all hurtling down the road on an office chair, wrapped in song?

Her response:

When you’re living in the land of the gifted and twice exceptional.

The enduring theme throughout Merrill’s book is brutal honesty about how hard parenting a 2E kid (each one “more unique than snowflakes”) can be. Yes, of course it’s also rewarding, invigorating, and often fun – but more than anything, Merrill argues, you’ll need to roll with the challenges each day, allow yourself a glass of wine before conking at night, and accept that parenting doesn’t look anything like what you planned it to be.

Actually, prior to becoming a parent, I don’t recall holding many preconceptions – but I CERTAINLY didn’t anticipate how bone-crushingly exhausting it would be. There’s simply no way to know the truth of Parental Exhaustion until you enter into those shoes for yourself. And with 2E kids, Even More So.

With that as my brief introduction, here are my take-aways from Merrill’s book:

Chapter 1: Connecting the Dots

Citing a commencement speech by Steve Jobs, Merrill notes that sometimes you can’t make sense of your child’s journey until you’re looking backwards and “connecting the dots” (p. 2). I love this framing of life as the narrative we create for and about ourselves: it empowers us to search for key points that may have seemed like insurmountable challenges, but turn into critical milestones in retrospect.

I also appreciate Merrill’s coining of “adult-onset, child-induced ADHD” – such a perfect description of what happens to even the brightest (perhaps especially the brightest?) of new parents. After admitting that she’s “been entirely unable to concentrate on one thing for longer than a few minutes” since her oldest (2E) son was born, she adds:

It’s just, well, I miss my brain. We used to go for long walks through thoughts together. Double-dated with new ideas. We used to dive into activities and barely take time to come up for air. Now my brain is crashed out on the mental couch, drooling a little, while I perch anxiously, waiting to spring into action, my Mom Radar spinning wildly 24/7 (p. 7).

This was exactly how I felt when my kids were younger, and I was desperately reaching out for daily support and assistance in as many ways as possible. Now that my kids are older, I’ve learned to tame my brain enough not to be on super high alert, given that quiet no longer means something challenging or dangerous is about to happen – it simply (ha!) means parental guilt that I’m leaving them to their own devices (literally).

Finally, Merrill offers a list of things she wishes “the world knew about parenting 2e kids”, including:

We are not making up this stuff (p. 8).

(This reminds me of how gifted kids can sometimes be “gaslit” into disbelieving their own uniquely intense reality, as described by Linda Silverman. Apparently the same is true for parents of 2E kids.)

Sometimes we appear over-protective, while sometimes we seem neglectful (p. 9).

(Every day, in every way, I need to continue to practice the art of – as my husband would put it – “not giving a f***” what other people think about my parenting decisions. As a former people-pleaser-extraordinaire, this has been a monumental challenge – one I’m still working on.)

Not every 2e kid has the same issues. Every single one of these kids presents differently, and they are not in parenting magazines or books, mainstream blogs, or general societal acceptance (p. 10).

(This is a sobering reminder of how isolating it can be to look at “mainstream” parenting sources and not see our own experiences and realities reflected – hence, the need for support groups, blogs, podcasts, and books specifically for parents of 2E kids.)

Chapter 2: One Heck of a Ride

In her second chapter, Merrill responds with brutal honesty to the quip “Must be nice to have a gifted child” with her own “must be nice” rejoinders:

Must be nice to have a child whose racing brain doesn’t keep her awake into the wee hours (p. 13).

(My 12-year-old C has “insomnia issues”, just like me. In addition to endlessly racing minds, we each have our own laundry list of hacks and supports needed to help us fall and stay asleep. I’ll write more about insomnia in another post.)

Must be nice to not have to worry about your child making and keeping friends (p. 13).

(My number one wish for my 10-year-old neurodiverse son D. is that he’ll finally make a new and trusted friend this year – not exactly easy during a pandemic.)

Must be nice to take your kid somewhere new and not worry about having to leave early because of over-stimulation (p. 14).

(Heck, I’ve always just assumed we won’t stay long! We aim for an hour, and anything beyond that is bonus.)

Also included in this chapter is a hypothetical letter written by Merrill to her child’s teacher (“You have too many students, not enough time, and there’s just no money to do anything different… Trust that I wouldn’t tell you how he learns unless I thought it would help you help him.”), and Merrill imagining what her own Gifted and Talented Conference opening speech might sound like (“Parents, you need to remember to take care of you.”)

Chapter 3: Taking the Leap

Here, Merrill talks about “taking the leap” to homeschooling her 2E son. In a hilarious passage, she compares a series of statements said by a teacher to “what’s actually meant” and “what is heard” by the parent on the receiving end:

What is said: Your child refuses to participate in any class activities and will not put down a single word, even when given the words to write.

What is meant: Your kid is the most passive-aggressive ODD child I’ve ever known and I haven’t the slightest clue how to motivate him…

What is heard: Your parenting skills are just below those of a psychotic hamster. (p. 31)

I resonate with Merrill’s insecurities. Like her, I was formerly a classroom teacher, and well remember what it was like to feel frustrated and exhausted by “out of the box” kids who, quite simply, made my job a lot harder. Now, as a parent, I’m constantly walking a fine line of wanting to empathize with teachers while also advocating for what my kids need – and hoping I come across as just-the-right-mixture of humble-but-proactive-and-informed parent. It’s tricky.

Chapter 4: Our Grand Homeschooling Adventure

When discussing her experiences with homeschooling (only chosen as an option when her designated gifted kid was denied services at his new local school due to his twice-exceptionality), Merrill shares:

I am not a patient woman. I know this about myself and barely accept it. I walk fast, I talk fast, and I want to scream when my computer isn’t as caffeinated as I am (p. 36).

Hear, hear. My nickname as a kid was Speedy (no joke), and it remains insanely challenging to slow down enough to roll with the ride of parenting and accept imperfection on a daily basis. I may know (hypothetically) all the things I “could” be doing with my kids to optimize their learning experiences, but constantly have to settle for the reality of how much I actually get done – because ultimately, self-care trumps even the illusion of “parenting perfection”; nothing is more important.

Chapter 5: Living My Walter Mitty Fantasy

In her final chapter – after singing the praises of Pixar’s The Incredibles (2004) as the ultimate cinematic representation of a gifted family (love that movie!) – Merrill notes that back in her pre-kid days, as a professional flutist, she was actually living her “Walter Mitty fantasy” – that is, her daydream of a perfect alternative life. Now, as a parent of a 2E kid, she vacillates between loving and hating the work she has cut out for herself:

I love homeschooling my son… I don’t miss the fights over homework, the breathtaking anxiety about his psyche, or the conferences with teachers about everything he was doing wrong and nothing about what he was doing right.

I hate homeschooling my son. It’s all on me. (pp. 55-56)

Yes, exactly. I’m thrilled that during this learning-at-home pandemic time, it’s actually not “all on me”: I get to do a mix of both, with my kids’ teachers determining their curriculum (for better and for worse – but mostly for better), and it “simply” being up to me to supervise them and make sure it all gets done.

Back when I first attended a SENG parent support group, our facilitator reminded us repeatedly that there’s never a perfect solution to our kids’ schooling needs – there’s only compromise and striving for the “best possible”.

That’s certainly been my own experience, with plenty of highs and lows over the years. So much depends on the grace, understanding, and flexibility of our kids’ teachers – and, like Merrill, I “stand with teachers” (p. 38) while also standing with students and parents.

I appreciate Merrill’s closing reminder in her book:

“If you decide to confide in others, you’ll discover you’re not alone” (p. 58).

Speaking of that, last night I participated in a webinar and support group for parents of gifted kids (hosted by the Institute for Educational Advancement), and got multiple dopamine hits from having my experiences and challenges validated again and again – ping, ping, ping.

I was reminded that the more we come together and share honestly – as Merrill does in this book – the happier (and less alone) we’ll be.

References

- Merrill, J. (2012). If this is a gift, can I send it back? Surviving in the land of the gifted and twice exceptional. Gifted Homeschoolers Forum Press.

Copyright © 2020 by HalfoftheTruth.org. Please feel free to share with attribution.