Episode 1: Check-In

We’re officially one year into the COVID-19 pandemic, and life continues to throw interesting curve balls nearly each week.

My three twice-exceptional kids – daughter C. (12 years old), son D. (10 years old), and daughter I. (8 years old) – have all been learning from home by Zoom with their public school teachers since March of 2020, with a few months off during the summer to recharge.

Given the limited schooling options available during a global health crisis (there are no perfect solutions), I’ve made peace with certain aspects of the remote learning model offered by our district, while accepting that others aren’t “good enough” by any stretch – but nonetheless simply “are what they are” for now.

So, how are we all doing?

My younger two kids, D. and I., seem to be relatively okay. (More on them in a moment.)

C., however, is not. She has stated openly that she wants and needs to be around same-age peers and with her teachers in person. She repeatedly rejects remote learning as “not school”, and has begun taking out her frustrations in passive-aggressive ways. I can’t really blame her (what else can a person do when they literally feel powerless?) but it’s hard to work with.

After receiving a caring but alarming email last week from one of C.’s teachers that she wasn’t even opening up her assignments during synchronous class time (let alone turning them in), C. admitted to me that she feels angry. I told her that made complete sense. There is a heck of a lot to feel angry about these days, especially as a teen or pre-teen.

Online learning simply isn’t C.’s “thing” – and, this many months into pandemic schooling, I don’t anticipate that changing. It seems she will continue to put in just as much work as necessary to get by and keep us off her case – but, she’s not really buying it. (I should add that she doesn’t want to switch to homeschooling – I’ve offered that option numerous times.)

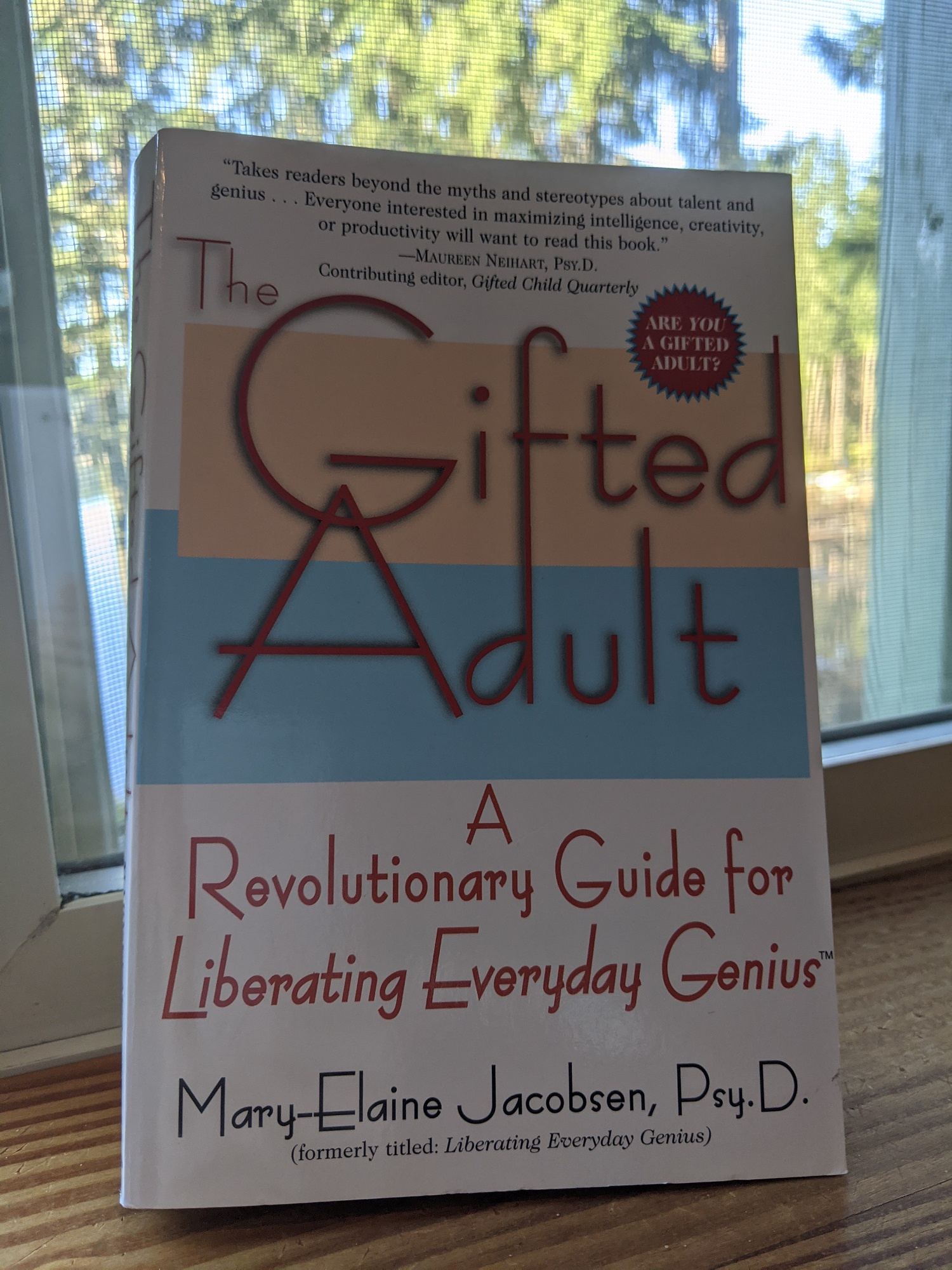

It would be hypocritical of me to blame C. too harshly, not least because 12 years old is when I first bowed out of formal schooling, too (albeit in a very different context). Some form of “school refusal” may be in our future with her, and I think I’d better buckle up for that surprisingly common gifted-kid ride.

Speaking of choice in schooling during COVID-19 . . . This leads me to a quick story about how I’m doing with everything pandemic-schooling-related.

Episode 2: Vertigo and Return to In-Person Schooling

Given our nation’s disastrous response to the pandemic last year – as well as our district superintendent’s stated commitment to making data-informed decisions – I assumed that we should expect our kids’ schooling to remain remote for the rest of the school-year. A lot of time and energy has been put into “doing online schooling well” in our district, and it’s abundantly clear how committed teachers are and have been to this process.

Despite recent guidance from the CDC on how to safely open schools, I figured it would take at least until summertime for us to reach appropriate levels of safety for this to occur – and that it would actually be a pedagogical and emotional error to mix things up for our kids at this late stage in the game anyway, now that they’re finally used to the routine of online learning.

However, a few weeks ago all parents in our district received a surprising email late one Friday afternoon from our superintendent (not vetted or seen by teachers ahead of time – but that’s a whole other can of worms), detailing plans for gradual hybrid re-opening of schools for students in grades K-5 – within the next few weeks.

Zoing!!

This message felt completely out-of-the-blue, and threw me for a serious emotional loop. I didn’t quite know how to process it, so I simply “set it aside”, mentally-speaking.

Later that evening, however, I developed rapid-onset, extreme vertigo. When I tried to get up out of bed, the world starting spinning around me. It was challenging even to get up and go to the bathroom. I went to sleep early that night, hoping and praying that by morning the vertigo would simply be gone, or at least lessened.

But, no. It was still there with a vengeance when I woke up on Saturday morning, and persisted throughout the day. I felt cautiously better by Sunday, incrementally better on Monday, and about the same on Tuesday – at which point I finally (randomly) made the time to talk with my younger sister, A. She and I were chatting away, and as soon as I shared about my vertigo (which hadn’t quite left – it was still lurking mildly in the corners, ready to pounce at any moment), we were busily trying to figure out its cause. Could it be:

- COVID?!? (it’s now a known symptom)

- Peri-menopause? (I’m getting older, and hormones are tricky business)

- My husband’s latest 3D printer? (the smell of burning resins was strong enough that my 12 year old fainted the other day after helping him out)

We strongly suspected this third idea, though my husband pooh-poohed it, talking about materials safety data sheets, etc. Then suddenly I said to my sister:

“Oh yeah! There was something else that crazy day!”

(The Friday before my vertigo onset had been an unusually busy one, with virtual meetings taking me from talking with new colleagues in Turkey in the morning, to meeting with a formerly incarcerated student in the afternoon, to attending a spoken word performance as the final plenary session of a five-day online conference on providing higher education opportunities in prison in the late afternoon – all sandwiched in between making sure my kids were reasonably on track with their schoolwork, we were eating meals, and I was getting sufficient work-work done.)

However, as soon as I shared with A. about the email from our district, things started clicking.

A. teaches Kindergarten remotely in a large urban school district, has a medically fragile husband, and is caring for their highly gifted five-year-old daughter from home in their small condo. She “gets” the insanity of the choices we’ve all been asked to make for months now, both as a teacher and a parent – and commiserating with her about how freaky it felt to receive such unexpected news about our district’s pivot to in-person seemed to have a semi-miraculous effect on my brain. I could feel the last dredges of my vertigo fading away.

It seems that by talking openly with my sister, I was able to remind myself on a visceral level that I still – at least to some extent – have control over what happens with my kids and our household. I have the ability to choose whether they’ll go back to in-person schooling (or not). Like nearly everything these days, our decision will be a frustrating compromise – but the important thing is, we do have a say of some kind.

Episode 3: What Now?

Another curveball was suddenly thrown into the mix a few days ago, when our governor issued a mandate that all schools be prepared to welcome all K-12 students back in-person, stat – as in, grades K-6 by April 5 and grades 7-12 by April 19.

Whoa.

A quick skim of an online community discussion forum for parents in our district served as a potent reminder of how widely we differ in what we believe to be best for our kids, all of whom are surely hurting in some way, small or big. Many families on this forum were crying tears of joy due to this new mandate. Going back in-person is a no-brainer for them – something they’ve been waiting for and wanting for months. I had no idea.

After careful deliberation, my younger kids have both decided to stick with remote learning for the rest of the schoolyear:

- I. has taken to saying in recent weeks, “Raise your hand if you’re used to Zoom for school!” which is simultaneously sad and deeply heart-warming to hear. I.’s hard-working, compassionate teacher has helped I. develop a tentative sense of security around what to expect each day during online schooling (and she loves it that I’m also there to help her as much as I can, in between work).

- D.’s challenges as a neurodiverse kiddo are different – but he, too, prefers to stay at home for school, for two self-stated reasons: a) he can sleep in rather than getting up early to take the bus, and b) he doesn’t need to worry about others hearing or smelling bodily functions (!). (This latter reason was brought up my husband as a perk of working from home . . . I will leave it at that.) I am still (always) concerned about ensuring D. develops friendships and relationships with peers – which he hasn’t, really, in his new online class – but sadly, I’m not at all confident that returning in-person right now would allow for this to happen, either. I will need to continue exploring other options (i.e., interest groups) to help him out on that front.

- My daughter C., however, may very well be going to school part-time in-person, in whatever fashion that looks like. We’ll leave it up to her, but if she’s comfortable taking that risk, we will support her. I sincerely believe she can manage the safety protocols, and might begin (fingers crossed) to feel some of the joy she used to have around middle school, rather than simply tolerating it.

In this stressful Russian roulette of pandemic schooling models (what’s the appropriate risk-benefit ratio, and how will we know?), it seems ideal if we can each choose what we believe is best for our own family and kids, within reasonable public health constraints and concern for everyone’s safety – especially given that the mental health toll on kids during this pandemic has been mind-boggling.

No, that’s not the right phrase – it’s not “mind-boggling” because it actually makes sense; let’s call it beyond-comprehension. C. was already diagnosed prior to the pandemic with clinical anxiety, and has now also been visibly depressed, despondent, and listless for months. (Not all the time, and not to the point of serious concern – but it’s nonetheless deeply distressing to see unfolding.) As resilient as kids are – and thankfully, they really are – we (collectively) will be dealing with the fall-out effects of this pandemic for years to come. There are no perfect solutions by a long stretch.

So, even though the idea of C. returning part-time to in-person schooling freaks me out after so many months of trying to keep us all safely within our bubble, I’m willing to try a reasonable new option, for C.’s sake – if she wants to. It can probably be done.

We’ll just have to see how thing go.

NEXT DAY UPDATE: As of today, having talked through all options with C., she prefers to stay home for the rest of the year. Once again, we shall see . . .

I’ll return later with another post on more of the specific challenges C. has faced while navigating online learning, and some strategies I’ve been using to support her.

Copyright © 2021 by HalfoftheTruth.org. Please feel free to share with attribution.